- Women’s football in England continues to rise, but working-class kids missing out

- Generations of inner-city talent being lost as training centres inaccessible

- Should centres and academies leave the suburbs in search of a home in their cities

Transforming Women’s Football in England: Bridging the Class Divide for True Growth

The Middle-Class Nature of Women’s Football in England

Women’s football in England is a middle-class sport. For the game to grow, it has to change.

Generations of working-class kids are missing out on elite women’s football in England. It’s off-putting for the fans.

The Rise of the Lionesses and the Shift in Attention

Women’s football in England has never been in a better place. For years, there had been a steady increase in attention on the women’s game, but nothing could quite prepare loyal fans for the juggernaut of attention following the Lionesses winning the 2022 Euros.

It turned players into household names with their faces plastered across buildings and interviews in national newspapers. It led to new sponsorships in the domestic leagues, more money being spent on facilities, government investment at grassroots level, bigger transfers, bigger TV rights deals and a year-on-year increase in both attendance and viewership.

But there’s something still not quite right about the women’s game.

The Working-Class Gap in Women’s Football

Perhaps the gap between the top teams and the rest of the league hinders its development. Perhaps it’s the uncontrollable abuse online directed at the players.

Or perhaps, English football is missing out on one key driving factor in success that men’s football has an abundance of: working-class players.

Women’s football in England in many ways is the complete cultural opposite on that front.

In England, the women’s game has always been middle-class whereas the men’s is deeply rooted in working-class culture.

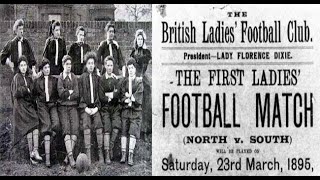

Historical Context of Women’s Football in England

The British Ladies Football Club – formed in 1894 was pushed and funded by upper and middle-class women, who wanted fellow middle-class women to become professional footballers.

These women were often mocked by the press but routinely drew in crowds of thousands. Their success saw football clubs allowing women to watch matches for free by 1885, and by the late 1880s, due to the success of the scheme, women had to pay full price to attend matches.

By the time of the First World War, there was another uptick in women’s football as many women – now working in factories whilst men were away at war – started playing football during their lunch breaks. It became so popular that the factories organised a league.

Then Prime Minister David Lloyd George encouraged women to play during this time as it helped with the war image he wanted to create. That the women were strong, capable and able to do the ‘jobs of men.’

But where do working-class women fit in all of this? In The British Ladies Football Club, women from poorer backgrounds simply did not have the means to travel or the time to train. Much of their existence was marred by financial hardship and their lives were dedicated to family and work.

By the time of the war, working-class women were starting to enjoy playing football and the game was becoming so popular that teams were starting to be played on the abandoned football grounds.

On Boxing Day 1920, Dick Kerr Ladies played St Helen Ladies at Goodison Park, drawing a crowd of 53,000 spectators.

In 1921, the FA banned women’s football.

Now, more than 100 years on from the ban, women’s football in England could hardly be in a better place.

But working-class women have since disappeared from the game once again. Where have all the working-class kids gone?

Barriers Faced by Working-Class Women in Football

It’s always been tough to find your feet in football for women, with the working class at an extra disadvantage.

But there have been spells in the game that have shone a light on a more diverse lineup.

In the 2007 Women’s World Cup nearly half the 21 players were from inner-city areas and low-income households.

It’s understood that out of the 23-player squad chosen to play the friendly against the USA in November (a drab 0-0 draw in front of 78,000 at Wembley), only four players came from the same background.

The traditional route to elite women’s football came (generally) through attending a centre of excellence. They were set up in the late 1990s – often near the inner-city club grounds and were designed to help girls develop from school football to the next level.

These centres, for the best part, worked. England saw the emergence of the likes of Anita Asante, Alex Scott, Casey Stoney and Fara Williams to name a few.

Current Accessibility Issues in Women’s Football

But many of the centres ended up being moved to the men’s training bases which are often in suburban areas. Arsenal football club may be a working-class, north London, inner-city team. But they don’t train there. They train in the leafy suburbs of St Albans in Hertfordshire.

It’s the sort of area working-class kids cannot afford to reach.

The 2022 success of the Lionesses didn’t do much to change this. The FA set up 73 Emerging Talent Centres (ETCs) to replace the centres of excellence with the aim of reaching more female talent across the country.

They – like the centres of excellence – are still in hard-to-reach places especially if you’re relying on public transport. With the average salary in the Women’s Super League at £47,000 compared to £3 million in the Premier League, there is less incentive for families to sacrifice time and resources in getting their girls to these centres. In that sense, women’s football still feels less like a realistic career option and more of a hobby.

Emma Hayes’ Vision for Inclusivity

Former Chelsea boss Emma Hayes spoke of her fears that generations of inner-city talent – like those raised playing in the south London cages – are being lost due to inaccessibility. Hayes, a working-class Londoner, said the current system of academies should be abandoned in favour of bringing coaching and development into the inner city.

“Women’s football is quite a middle-class sport in my opinion,” Hayes said.

“In terms of the locations, the pedigree of player, they’re often coming from suburban belts around the training grounds. They’re not the Alex Scotts, the Rachel Yankeys, the Anita Asantes. They’re not coming to our facilities in the same way and you’ve got to ask yourself the question: why?

“Look at the number of footballers that came out of south-east London and into the England men’s team; an unbelievable number. Why aren’t they in the women’s side? I often ask that question [at Chelsea]. They’re all from Surrey. They’re the most talented kids in Surrey. But are they the most talented kids around? I beg to differ.

“Why aren’t we going into London? Why aren’t we hosting our academies right in the heart of London? Who in their ivory tower has been dreaming up this prawn sandwich girls football club?”

Lack of Diversity in the Women’s Game

The lack of diversity in the women’s game is holding back the growth of the game. There is a link between socioeconomic background and ethnicity, with many from the inner cities likely to be ethnically diverse and poorer than those from suburban or rural areas.

The majority of loyal football fans in this country are working-class and it’s important for fans to see players from lower socio-economic backgrounds to ensure they remain interested in the game.

The lack of access working-class kids have will always hold back the development of the Women’s Super League (WSL) and the England National Team – the Lionesses.

When you can only pick from a small pot of players, you have limited yourself. And as the game continues to grow around the world, England needs to expand its reach to draw even more talent into women’s football.

The success of the Lionesses over the last few years should have been a catalyst for change and in many ways, it has been.

More and more women and girls have started playing football since the 2022 win, and there has been a 239 per cent rise in attendance at WSL matches between 2020 and 2024.

But as all eyes are focused on making sure the top leagues become more and more professional and that the players and staff have what they need to succeed, those making the decisions appear to have skipped over an important step.

They have not yet figured out how to open the professional game up to a wider audience, they have not figured out how to diversify.

“We’ve still got a lot more to do from the grassroots talent pathway all the way to elite level.”

Karen Carney, former England and Chelsea player

“If you look at the stats, the game is thriving. Imagine what it could be if we gave it even more.”

Future Steps for Women’s Football in England

It’s now been over 100 years since the FA banned women’s football in England and the domestic league is not only fully professional but more than 3.4 million women are playing at grassroots level. There have been some major milestones along the way, and this recent crop of English talent has much to be proud of.

With more investment and a wider reach, England can establish the WSL as the major league of the women’s game and, much like the Premier League, could see it become an international business that contributes to the UK economy.

Former England and Chelsea star Karen Carney said: “We’ve still got a lot more to do from the grassroots talent pathway all the way to elite level.”

“If you look at the stats, the game is thriving. Imagine what it could be if we gave it even more.”